A Celebration of Spring

In an age of mass produced pap, Latvian painted Easter eggs are a burst of delightful, do-it-yourself spirit. In kitchens across the land, the generations get together to create beautiful patterns and colours on what is both a staple food and a potent symbol of birth and renewal.

And have a bunch of laughs cracking them open.

It's also interesting to reflect on the history that underlie these good times. Because like the eggs, Latvia is home to a kaleidoscope of different faiths that blur into a fascinating whole.

Son of God or sun as god?

Latvia has historically been Europe's easternmost outpost of Lutheranism, most northerly bastion of Catholicism, and the point furthest west where Russian Orthodox believers have put down roots. Throw in strong pagan traditions (due to the fact that all these Christians arrived rather late), and you have a rich religious stew.

It gets particularly delicious at Easter. As this medieval moulding of a knight kneeling before Christ in Old Riga shows, the Biblical story has been well absorbed over the centuries.

But it shares the stage with even older rites. So, many Latvians will go to church on Easter Sunday (though plenty of others will enjoy a welcome holiday snooze). In any case, everyone will eventually gather with kin for some willow-branch whacking, egg painting, high swinging heathen good times.

Red letter days

First we need to delve into some dates.

The original Christian Easter drama took place on the Jewish Passover almost two millennia ago. But in 325 AD, the Council of Nicea moved the holiday to the Sunday after the first full moon following the Spring equinox so it wouldn't be held on the Jewish holiday (though curiously, in 2022, Easter Sunday, Passover and the Islamic Ramadan were actually concurrent).

This means that Christian Easter Sunday can fall anywhere from March 22 to April 25. And incidentally, until the 16th century, in most of Europe the New Year was taken as starting in March.

But however much humans may try and impose their rules, nature follows its own agenda. The Vernal equinox, when the day and night are the same length, arrives around March 21 (it can actually fluctuate by a few days). This brings light, a new rush of life for countless plants and creatures, and joy to human hearts as winter finally releases its grip.

And that is what Latvians have been celebrating at Lieldienas (literally, the "Great Days") since time immemorial. Even if these days, the triumphant ascendancy of spring is marked around the time of Christian Easter.

A good whipping

The festival gets underway on what Christians call Palm Sunday.

As anyone who has been in a Latvian pirts can attest, things get physical when there are bundles of branches lying around. And as with sauna switches, it is believed that spanking each other with willow twigs on Pūpolu svētdiena (Willow Sunday) can impart a dose of natural goodness into the receiver.

The first person to get up in the morning grabs a handful of the twigs, then runs around giving the layabouts a good thrashing on the behind. Invocations to "let the health in, let the illness out." The intentions are noble - it is believed that those thus wakened will sleep well during the summer - but of course there's an element of mischief, too.

As the writer and artist Jānis Jaunsudrabiņš (1877-1962) reminisced about his childhood Easters in Nereta Parish, southeast Latvia: "Having in the course of the year received no shortage of spankings, deserved or not, I relished the chance to get up before sunrise on Willow Sunday and give everyone a beating, even my mother."

After this frivolity, Jaunsudrabiņš recalled the master of the house would read from the New Testament about Jesus' entry into Jerusalem, with adoring crowds laying palm branches in the path of his donkey. Botany is another bridge linking the two traditions.

Time to dye

In the old agrarian society, the final month of winter meant belt tightening as last year’s food stocks ran low. With fond relish, Jaunsudrabiņš recalled a special treat on Willow Sunday. Pītes, balls of grey peas, hemp seeds, onion and a little pig fat, truly hit the spot during the hungry days.

So with the coming of spring, as the cows began giving milk and the chickens started laying again, the relief was palpable.

Most of us today have full bellies all year round. But whose heart doesn’t flutter when they can finally put the heavy coat away, and get a break from horrific heating bills? Time to add some colour to life!

Recipes handed down the generations vary. But your typical Latvian family will boil up water, with onion skins added for colour. White eggs are wrapped in ferns, moss, small leaves, pine needles and other garden bric-a-brac, then boiled in the water, producing an amazing array of hues and patterns.

On Easter Sunday, folks take it in turn to bash their eggs against the others. The winner enjoys bragging rights about having the strongest ones. With inuendo around the fact that olas (eggs) is also slang for testicles. But it's all about fertility, right?

Hidden meanings

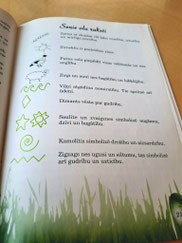

Enough tittering. Because there's more to the patterns than meets the eye. The book "Lieldienas" (editor Ineta Bērziņa), a tome rich in all things relating to Latvian Easter, provides an intriguing guide to the meaning of symbols either carved into the shells of painted eggs, or which serendipitously appear:

- pine needles promise good health, stamina and eternal youth

- a spider is a sign of patience

-

a bird means all wishes will come true, plus fertility

- horses and rams bring wealth and prosperity

- waves mean immortality

-

diamonds are wisdom

- the sun and stars promise growth, life and wealth

- a ball assures security and protection

- a zigzag represents fire and warmth, as well as wisdom and faithfulness

Eggs are also painted by many other cultures around the world. And according to folklore scholars Marģers and Māra Grīns, the tradition may have come to Latvia from Germanic tribes to the west. They cite one of the dainas, ancient Latvian folk songs, using the loan word pervēt (to paint) rather than krāsot.

But before anyone's ethnic pride is hurt, it doesn't matter. Cultures borrow liberally from each other, then produce their own unique interpretations. And few do Easter eggs with more dazzle than the Latvians.

Likewise, chocolate Easter Bunnies are a recent borrowing from the West. But a good old hunt around the house to find where the hopping visitors (precociously fecund symbols) have hidden eggs is enjoyed by many a Latvian youngster.

Ups and downs

By Easter Sunday, Quiet or Holy Week was over and it was time for unabashed fun. So in olden days as now, folks take a ride on specially constructed swings, called šūpoles, confident that this ensures fewer mosquito bites in summer.

One folk belief has it that you should always let the swing come to a stop by itself so your flax would grow properly. Another cautions that once you have put up a swing on your land, you have to do it every Easter, or else you'll attract bad luck.

However, this wasn't how things were done in Jānis Jaunsudrabiņš's neck of the woods, where the surrounding farms would take it in turns doing this Easter chore, then invite all the neighbours around. The writer recalled laughter and song as friends caught up and took turns on the sturdy swing his uncle had crafted from old beams in the barn. The builder was also the main pusher of the contraption, who for his trouble got gifts of painted eggs.

Fewer people build their own these days, but most municipalities set up public šūpoles for everyone to enjoy. Amidst the merriment, Ineta Bērziņa poses a profound question in "Lieldienas": does the upward swing symbolise the sun's ascendance? Or the resurrection of Jesus?

For Latvians it can be both, with no fear of contradiction.

Spread your wings!

There is one Latvian Easter tradition that is unapologetically, one hundred percent pagan.

The Livs (or Livonians) are an ancient people speaking Finno-Ugric language who have assimilated over the centuries with the Latvians. In recent decades, there has been a revival of Liv culture, including the spring equinox tradition of “waking the birds.”

The Livs believe that rather than flying to distant lands in winter, the birds are asleep by the seashore. So at the equinox, they go to the beach and make a big racket to wake them up.

For added measure, the birds are believed to embody evil spirits and witches. So better to chase them into the forest where no harm can be done. Naturally, singing and feasting are also part of the programme.

Below, the folklore group Dvīga shows how it’s done in Saulkrasti.