Live and let Liv

With just 31 people per square kilometre, Latvia is one of Europe’s most sparsely inhabited countries. And in the most remote corner of this land of haystacks and birch groves, you’re more likely to meet a moose than another human being.

Welcome to the Livonian Coast - 12,000 hectares of wilderness with just 746 full-time residents.

If you’re into cocktails and deckchairs, the dense forests, pristine beaches and scattered village won’t be your cup of tea. But if you long for nothing louder than sea gulls and lapping waves, this Baltic Garden of Eden has all you need.

Plus a few sights straight out of a Star Wars movie.

An ancient tongue

Framed by the Baltic Sea, the Gulf of Riga and Slītere National Park, this lush backwater stretches some 20 km from Ģipka south-east of Cape Kolka, then 60 km south-west to Oviši.

Today, the seaside hamlets are largely the preserve of holidaymakers from the city. But they have a rich history stretching back millennia.

About 5,000 years ago, as the glaciers from the last Ice Age receded, people speaking a Finno-Ugric came to Latvia to hunt reindeer. These Livonians (or Livs) settled along the Gauja River in Vidzeme, and also became fishermen in northern Kurzeme.

A bit later, tribes of Balts arrived. Over many centuries, the two groups blended together and formed the Latvian nation. It was more of a friendly merger than a hostile takeover. Although Latvian is part of the Baltic language family, it contains many Finno-Ugric words, and Latvian cultural icons like the folk song Pūt vējiņ! were originally Livonian.

But on the north-west coast, the Livs kept their separate identity well into the 20th century. The documentary Livonian Songs offers a fascinating glimpse of this community in the 1970s.

Big Brother at the beach

The Livs were hardy folk who endured plagues, storms and brutal winters. However, the harsh Soviet occupation was the final straw in their extinction.

Latvia's west coast formed the western border of the USSR. So, fishing was banned, and severe restrictions were placed on people entering or moving around the area. The beaches were raked at sunset to show any footprints of people escaping the workers' paradise, or foreign spies trying to get in.

The film “Kurpe,” a drama revolving around a shoe found on the beach by Russian border guards, reveals the degree of the regime's paranoia.

The coast is still dotted with bunkers and other military relics.

And at Irbene on the southern edge of the region, a Cold War monument looms out of the forest that will have you scratching your eyes, wondering if you are hallucinating.

Used to spy on NATO communications, the 32-metre-diameter Irbene Radio Telescope was so secret Latvians didn’t even know about it until the 1990s. Many other Soviet military installations were looted by departing soldiers and local metal scavengers. But this monster survived thanks to a band of dedicated scientists, and is today part of a European network of telescopes exploring black holes.

A remarkable swords-into-ploughshares achievement. You can visit the big dish and an underground tunnel connecting it to a smaller instrument by booking ahead on +371 2923 0818.

Rebirth of a nation

A few years ago, the last stretch of the Ventspils-Kolka road was asphalted, so cruising up the coast is now a breeze. Especially compared with the prewar days, when rare visitors came by boat or a narrow gauge railway built by the German army during the First World War. The line is long gone, but you can ride one of the old trains at the Ventspils Seaside Open Air Museum.

There's a string of tiny villages north of Ibene. The biggest of these, Mazirbe, is the cultural heart of the coast. Its community Hall, built in the 1930s with support from the Livs’ linguistic siblings, the Finns and the Estonians, houses an interesting historical exhibition. And in a major change to the longstanding cook-or-starve, situation for travellers, there's now a cafe serving excellent wood-fired pizzas.

This is one of the few nods to globalization in what still feels like a very isolated part of the world.

Near Mazirbe's beach, check out the evocative “boat cemetery,” a collection of old fishing craft whose fate mirrors that of the Livs themselves.

The last native speaker of Livonian, Grizelda Kristiņa, passed away in 2013. But since Latvia regained its independence, there has been a revival of the songs, customs and language of the Livs. Hence signs are in both Latvian and Livonian (with English in some places, too). The green-white-blue Livonian flag (symbolising forest, sand and sea) flutters in the breeze. There’s an annual Livonian festival in Mazirbe for people rediscovering their Livonian identity, and Livonian writers are turning out literature. Some of it has even been translated into English.

North of Mazirbe, pop into Košrags, Pitrags, Saunags or Vaide. Take in some of the fine old timber buildings. Laze or hike on the beach. You can go miles without seeing another soul. If you want an all-over tan, this is the right place.

In between swims, indulge in some forest bathing. Then get back to the seaside to escape the mosquitos.

The call of the sea

When you’re ready, by two legs or four wheels, proceed to Cape Kolka.

This tip of dry land where the open sea and the gulf meet may not seem like the centre of much. But the 19th century father of Latvian seafaring, Krišjānis Valdemārs, measured the contour lines between the northern, southern, eastern and western extremities of Europe, and concluded that Kolka was bang in the middle of the continent. Eat your heart out, Brussels.

It’s certainly on a busy shipping lane. The Irbe Strait between the cape and the Estonian island of Saaremaa is so narrow you get Estonian mobile coverage on the Latvian side. And its treacherous waters are one of Europe’s most infamous shipwreck sites, claiming an estimated 1,500 vessels over the last millennium.

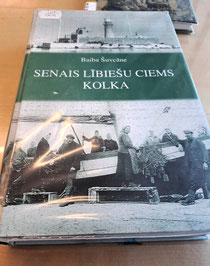

Some of these catastrophes are recounted in the book Senais lībiešu ciems Kolka (The Ancient Livonian Village of Kolka) by local historian Baiba Šuvcāne.

For example, on the night of 20-21 September, 1625, a squadron of ten Swedish ships departed from Riga for Stockholm. A storm blew up, they got lost and seven of the vessels were sunk or stranded at Cape Kolka.

When Admiral Clas Larsson Fleming made it to Stockholm with the three surviving craft, he sent a message to the Livonians, imploring them to assist with rescue and recovery. And he warned them that any looters would “know the meaning of fire and death.”

His concern was well-founded, as the natives were notorious for lighting false beacon fires to lure ships to their demise. And they earned the nickname “leg cutters,” because that was reportedly the easiest method for stealing a drowned sailor’s boots.

To be fair, Šuvcāne details many other cases where the locals did all they could to help stricken seamen. And the locals welcome visitors today, for all the right reasons.

Planning your trip

- Mazirbe is just over 2 hours’ drive from Riga. There are no petrol stations between Ventspils and Kolka, so fill your tank before you go. Two buses a day run from Riga to Mazirbe via Kolka, and another couple from Ventspils to Mazirbe. Cycling is a great way to explore the area.

- There are small grocery stores in Mazirbe and Kolka, as well as several guesthouses and campgrounds along the Livonian Coast. The campground at Vaide has the added bonus of a museum of horns and antlers collected by the owner in the forest over many years (not from hunted animals).

- You can visit the lighthouse at Oviši as well as those further south at Užava and Akmeņrags. Booking is essential. Phone +371 2626 4616.