Magic and Murder

From broomsticks to black cats, witches have captured the imagination of people around the world. And they've been a part of Latvian culture for millennia, though not in the way foreigners might expect.

As the last Europeans to encounter Christianity, Latvian pagans revered folk healers with a rich store of magic powers, useful for both good and evil ends. The most famous ragana is the charismatic Spīdola from the folk epic Lāčplēsis, who reverses her dark impulses to help the Bear Slayer fight off enemies invading the Latvian lands.

Catholic missionaries began preaching in Latvia from the late 12th century, and in 1201 Bishop Albert of Bremen formally brought this wild periphery into Christendom.But outside the towns, the peasants continued worshipping at sacred oaks and making sacrifices to their gods, with little interference by the church in these "harmless superstitions."

The situation changed radically after the Protestant revolution. Martin Luther and other rebel clergymen fervently believed that witches in cahoots with the devil did great harm, and set out to enforce the Old Testament instruction, "Thou shall not suffer a witch to live" (Exodus 22:18). And for more than two centuries, witch mania swept the Protestant states of Europe and their North American colonies (to a far greater degree than in Catholic areas).

fires of FEAR

Lutheranism was adopted in Riga and the province of Livonia (or Vidzeme) starting from the 1520s, and a few decades later in the Duchy of Kurzeme and Zemgale.

At the time, western Europeans regarded the eastern Baltic as barbaric territory where witches, wizards and werewolves roamed. And the zeal to stamp out these abominations was heightened by a desire to finally bring the heathen peasants to the one true religion.

The first known witch burnings in Latvia occurred Grobiņa in 1559. In 1574, a Latvian woman named Katrīna was tried in Riga for witchcraft. A neighbour accused her of cursing him, "may you be dry as wood and naked as a finger." A short while later, a local woman's baby died suddenly, and Katrīna was suspected of causing it. More witnesses accused her of giving them poisoned beer, then using magic to cure them. She was burned at the stake.

Hysteria spread across the land, as personal feuds escalated into spiteful accusations of witchcraft. Under torture, suspects named "accomplices," and hapless residents of Riga and the surrounding rural areas were dragged before the courts.

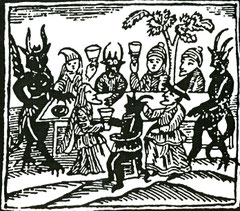

In 1584, Elza Miezīte was accused of flying at night and murdering children and animals before copulating with the devil on a hill at Daugavgrīva. She and 11 others were eventually executed, the first of several mass trials of witches.

Some of those accused would today be clearly regarded as mentally ill. In 1708, one Indriķis Veidemanis arrived in Riga from Germany. He had trouble with a moneylender, and began suffering acute anxiety. He said he was repeatedly approached by the devil, who offered to solve all his problems in exchange for his soul. Signing a pact with the Lord of Darkness with his own blood, he placed the document and a human bone outside St. George's Church (now the Museum of Decorative Art and Design). The cache was found the next morning by a soldier, who gave it to his commander, who in turn alerted the city authorities.

One notorious case blended the sacred and the satanic. In 1613, several peasants from Limbaži were tried for holding a meeting of wizards inside Doma Cathedral on Christmas Eve. The gathering had allegedly been presided over by the Devil himself, sitting on a high chair near the altar, wearing black silk garments and pointy black hats on each of his nine heads.

riga's macabre geography

The condemned peasants were subsequently burned in front of Doma Cathedral, where many other unfortunates met the same fate.

Witches were also burned at Karātavu kalns (i.e. Gallows Hill). Located at the western end of Stabu iela (literally meaning "street of posts," due to the many pillories and execution stakes set up there), the hill was where foreign criminals and poor city dwellers breathed their last (wrongdoing property owners were beheaded in front of the House of Blackheads).

Numerous skulls dating from the witch hunt era have been found while repairing water pipes on the corner of Skolas iela and Stabu. Ominously, the former KGB headquarters with its own brutal history is right next door.

A few kilometres to the north, witches were tested in Sarkandaugava, a branch of the Daugava River. Until the 19th century, this stream was called Soda grāvis (the Punishment Ditch). Suspected witches were tied up and thrown into the water. Those that floated had clearly been aided by the devil and were guilty. The ones that sank were innocent.

Historians estimate that around 50,000 people were burned in Europe during the witch craze.

Estimates of the total number in Latvia are hard to come by. But the scale can be gauged by the efforts on a certain Baron Netelhorst in Kurzeme, who alone had some 80 serfs burned at the stake. Little wonder that in Latvian folklore, landowning aristocrats are often depicted as devils.

rough justice

As the Enlightenment spread, educated Europeans began thinking more rationally about witches. In 1666, Doctor Urban Hjarne was appointed personal physician to the governor general of Livonia, a position which made him responsible for all military hospitals in the province.

A few years later, Hjarne was made an advisor to King Charles XII. After conducting an enquiry into witchcraft, he concluded that witches were just mentally unstable people. This led to reforms in Sweden and its Baltic territories abolishing the death penalty for most witchcraft cases and outlawing torture to get confessions.

The last witch execution in Riga was in 1692, and the final one in all Latvia occurred in Jelgava in 1721.

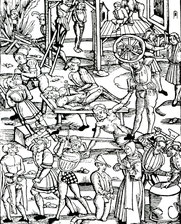

Admittedly, this was a brutal age for everyone, not just witches. For example, on 25 March 1594, Riga's public executioner submitted the following bill for services to the city's chief justice:

"Carrying out execution by the sword for Gertrude Huffner - 6 marks, execution for the peasant Tom - 6 marks, cut off ears and broke the bones of the thief Heinrich - 2 marks, broke the bones of the thief Mintz - 1 mark, execution for the thief Heinrich - 6 marks, hanging of the thief Marting - 5 marks, burning of a criminal for imprecisely weighing firewood - 1 mark and 4 shillings."

But the witch trials evoke particular horror, because they were perpetrated against people innocent of any crime, particularly women and the poor. And they set a horrific precedent for more recent orgies of hate unleashed by the powerful on their perceived ideological enemies.

With good reason, the question has been asked - why have we been taught to fear the witches, but not those who burned them?

latvian witches live on

In spite of these terrors, Latvians have never given up their pagan roots. And all over the country, witches are viewed in a friendly light:

- The village of Ragana, about 50 km east of Riga, boasts the "Raganas ķēķis" (Witch's Kitchen) bistro. Some Latvian bogs, forests and hills have the name "ragana." These are places they are believed to have lurked rather than execution sites.

- There's an impressive sculpture of a witch with a broomstick on the facade at Lāčplēša iela 100 in Riga (see the top photo.) The building dates from 1910 and was designed by architect Nikolai Jakovlev.

- A friendly witch greets hikers on the fairy tale trail in Tērvete Nature Park.

- According to folklorist Sandis Laime, country folk in northern Vidzeme and northern Latgale still strongly believe in "night witches." These ghosts of women who had unhappy lives lurk in cemeteries after dark.

- And scratch any modern Latvian and you'll find sorcery brewing. They gather herbal teas, pour water on hot sauna rocks to summon "spirits" and practice fertility rites at Midsummer.